|

ATTENTION:

THIS IS NOT AN

OFFICIAL WEBSITE. IT'S CONTENTS ARE THE WORK OF A

COLLEGE STUDENT, NOT AN ACCREDITED VOLCANOLOGIST,

SEISMOLOGIST, GEOLOGIST, OR ANYONE ELSE YOU SHOULD

ACTUALLY TAKE SERIOUSLY.

Colima’s

Consequences

“Don’t dance on a

volcano.”

-

French Proverb

Fig.

4.13 Ahh...what a beautiful mountain.

Vs.

Fig. 4.14 Fat Man, the

atomic bomb that

was dropped over Nagasaki during WWII.

Which one is

safer?

Fig.

4.12 An atomic bomb blast that bears an eerie

resemblance to Fig. 4.11 Fig.

4.12 An atomic bomb blast that bears an eerie

resemblance to Fig. 4.11

Want to guess

again?

Fig. 4.10

Eruption of Volcan de Colima

Not-So-Fun Fact

At the height of Mt.

St. Helen’s cataclysmic eruption on May 15, 1980, the

volcano produced the energy proportional to “one

Hiroshima size atomic bomb”14…

Every second.

A

case of

Jekyll and

Hyde:

Majestic Mountains/Violent Volcanoes

Lured by breathtaking, postcard-perfect scenery.

Beckoned by the challenge of a climb. Drawn by the

ultimate snow-draped ski slope. Enticed by abundant,

fertile earth.

There are a myriad of reasons why people

visit and inhabit volcanoes and the land that surrounds

them. To some, they provide recreation; for others,

subsistence. These farmers, avid adventurers, or simple

village-dwellers often do not realize the devastation

that even a dormant volcano is capable of producing.

Even worse, however, is that many are aware, yet they

shrug off the seismic shudders and sweep up the ash,

rationalizing, deceiving themselves of the danger.

Due to population pressures, the percentage

of people being forced into uncomfortable proximity with

the world’s volcanoes is increasing at an alarming

rate. Consequently, awareness of the awesome and

terrible power contained within these paradoxical peaks

is more crucial than ever.

Unfortunately, it is not

enough to know only that something will happen;

in order to avoid chronic paranoia, it is useful to know

what, when, where, and how it will happen, as well.

This is exactly the purpose and lofty pursuit of

volcanic monitoring organizations and volcanologists

around the world: making sure that no one ends up like

these guys…

Fig. 4.9

Pre-Hazard Maps: The aftermath of the 79 A.D. eruption

of Mt. Vesuvius.

An

Introduction to Ignimbrites

And

such.

First of all: just kidding - nothing is going to

be that technical. But if you are still wondering,

ignimbrites are “deposits of pumiceous pyroclastic

currents.”

14

Now, the average person does not know an ignimbrite from

a hyaloclastite. Even simply asking to pronounce a term

like jokulhlaups is probably too much, considering the

apparent difficulty some have merely in saying “lava” (lah-va,

not lay-va). Consequently, before throwing around terms

like tephra from a crater, a few definitions seem

necessary.

1.

Hazard. Implies the volcanic event, including its

nature and likelihood, as well as to whom and to what

degree it will have an impact. In other words, whether

you should run or not.

2.

Risk. The qualitative and quantitative measure of

the impact on the affected society. Basically, how fast

you should run, and if running will help you, your

house, or your cows.

Ok, so they aren’t that

technical, but the rest will be explained as they become

relevant.

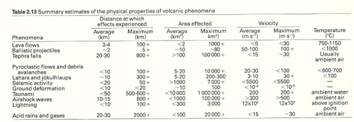

So what are the

risks and hazards associated with volcanoes?

The

Hazard

Handbook

Volcanic

Phenomena

larger

view

What Makes Them Dangerous?

larger view

And most importantly…

Can

one run away from them?

larger view

But no volcano displays

all of these behaviors…

Or do

they?

Fig. 4.11 Cheesy B-movie

Anyway…

so what are the risks associated with

Colima?

Danger: Defined

Suppose that you

are thinking of purchasing some property in the

foothills of Volcán de Colima. The real estate is cheap,

and the view from the valley is priceless. Yet you

might wonder if by living next to this volcano, you are

paying a much steeper price than you bargained for…

Who does this

information apply to?

Approximately

390,000 people live within 40 kilometers of the

Volcán de Colima13.

La

Yerbabuena, La Becerrera, Barranca de Agua, Rancho el

Jabilí, Suchitlán, San Antonio and Rancho la Joya, Juan

Barragán, Agostadero, Los Machos, El Borobollón,

Durazno, San Marcos, Tonila, Cofradía de Tonila,

Causentla, El Fresnal, Atenguillo, Saucillo, El Embudo,

Chayán, Quesería, Ciudad Guzmán, Tuxpan, Colima, Villa

de Álvarez, Comala, Cuahtémoc, etc.18

Hazard Maps

and

their Interpretations

So you don't

have to!

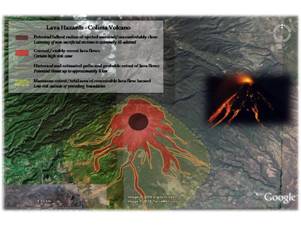

1.

Lava

(click for enlarged version and detail)

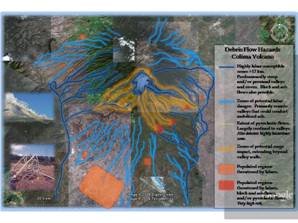

2.

Debris Flows

(click

for enlarged version and detail)

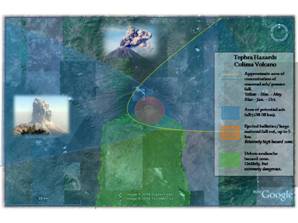

3.

Tephra

(click for

enlarged version and detail)

What should be

done?

Now that you have seen

the hazard maps, you might want to know what to do in

case you happen to be standing, traveling, eating lunch,

or even living within one of the hazard zones during an

eruption.

Besides run.

Sound advice, certainly,

but there is no need to pack up and flee the state every

time an eruption occurs. Inconvenience is to be

expected, but sometimes there are things that can be

done before and during an eruptive event to maximize

quality of life.

Such as not putting your

foundation in on top of recent pyroclastic flow

deposits, for one.

As an individual, here

is what you can do:

-

I'm an

English speaker and

I want to know what to do.

-

Hablo

espanol

y no se como me he llegado a este sitio, pero

quiero saber lo que debo hacer.

What about the

bigger

picture?

Well, in a

perfect world,

the risks posed by Colima could be reduced by:

a. Relocating everyone

within 500 km of the volcano somewhere else that is not

also within 500 km of a different volcano (in

Mexico, good luck...). This way, not even a little

bit of ash will affect them!

b. Constructing a giant

containing wall made of indestructible material around

the volcano

c. Filling in all the

valleys and damming all the rivers so that pyroclastic

flows and lahars will not be able to form

Alas, we do not live in

a perfect world or in a massively altered reality in

which any of those options would be monetarily,

physically, or even theoretically possible or plausible.

Therefore, risk must be

mitigated through more feasible measures.

First, if buildings or

cities exposed to volcanic hazards such as pyroclastic

flows and lahars, primarily, cannot be relocated, then

it is necessary to change the conditions that produce

these dangerous events. Although one cannot stop

the internally-driven production of ash by the volcano,

it is possible to change, to some degree, the external

elements that contribute to the formation of pyroclastic

flows and lahars. The easiest method would be

simply to deviate the channel, whether a valley or a

river, away from populated areas. However, it is

also understood that this could have potentially serious

consequences in areas reliant upon the water provided,

for example. Therefore, the best method is, as

always, prevention, for as the saying goes, an ounce of

it equals a pound of cure. On that note, all

construction should consider volcanic hazards. Bridges

over lahar-prone rivers or valleys should be constructed

so that their supports will not be exposed to damage

caused by large boulders or violent, thick, flows, and

should be substantially distanced from the banks, which

could collapse. This applies to other

constructions, as well - distance is one of the key

factors in preventing problems caused by volcanoes.

Infrastructure, such as electric, telephone, and

transportation elements should be sturdy and, obviously,

located as far as possible from the volcano itself and

from areas of potential danger. They should also be

capable of withstanding large quantities of ash in any

instance. Houses and other buildings, similarly, should

be constructed so as to avoid roof collapse, which is by

far the most common problem created by ash fall.

As always, a solid foundation of widespread education

and information dissemination is key - hazard maps

should be distributed, evacuation routes should be

well-marked, and the population should be informed of

the dangers associated with living in the vicinity of a

volcano. And this, of course, would not be

possible without constant, vigorous monitoring, aided by

the acquisition of the best technology and teams

possible.

Luckily, the risk to the

populations huddled around this volcano already appears

very minimal. Evacuations are very rare, and

substantial harm is usually inflicted only upon the

unfortunate livestock set out to graze on the flanks or

to the crops grown in the fertile soil where few

individuals would actually dare to settle.

Monitoring efforts seem adequate for the level of threat

presented and the largest zone of population is quite

well removed from the reaches of the hazards possible

today.

|