[35]

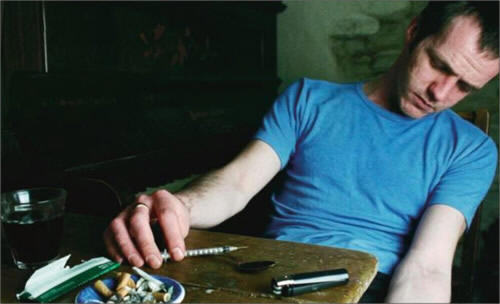

[35]In D.C. however, the boundaries between the major risk groups are less distinct. Considerable mixing occurs among different at-risk populations who engage in multiple types of drug use, high-risk needle practices, and unsafe sex. A disproportionate number of HIV/AIDS cases, most of which are associated with injecting drug use, have occurred among racial and ethnic minority populations of both genders [5]. Intravenous drug use is the second most common way HIV is spread among men in Washington, with unprotected sex being first. For women in the city, sharing needles is the most common mode of transmission [6].

[33]

[33]

Since the epidemic began, injection drug use has directly and indirectly accounted for more than one third of AIDS cases in the United States. This disturbing trend appears to be continuing. Racial and ethnic minority populations are most heavily affected by IDU associated AIDS. In 2000, IDU associated AIDS accounted for 26% of all African Americans, 31% of all Hispanic AIDS cases, compared with 19% of all cases among white adults. 57% of all AIDS cases among women have been attributed to injection drugs, compared with 31% cases among men [7].

Non-injection drugs, such as crack cocaine, also contribute to the spread of the epidemic when users trade sex for drugs or money, or when they engage in risky behaviors that they might not when sober. One CDC study of more than 2,000 young adults in three inner-city neighborhoods found that crack smokers were three times more likely to be infected with HIV then non-smokers [8].

Yet one of the biggest social and human consequences of the disease is precisely through its affect on the economy. In the rich nations of the west, it is clear that economic issues are a concern, but a manageable one. But in the poorest countries of the world,there is no dichotomy between worries about the economic development and concerns about human suffering. It only became apparent in the 1990s that HIV/AIDS is a significant economic issue. In the developed world, as new treatments emerged, health systems had to face the costs of purchasing them. In addition, the virus has the ability to mutate, which means that new treatments need to be developed all the time to cope with the virus’s resistance to previous drugs [9].In October 1995, AIDS ran up a tab of $75 billion already in the U.S. Now the life insurance cost is $200,000 [10]. In 1993, the U.N. estimated that Africa’s AIDS/HIV epidemic had already cost the continent $30 billion compared to the $75 billion in the U.S. Africa cannot spend as much money on treatment since the continent is not as wealthy as the U.S. The United Nations estimates that by 2010, AIDS will have reduced Africa’s overall labor force by 25% [11]. In the middle-income countries the average income is smaller, HIV prevalence tends to be a little higher than in the richer nations, and the virus is spreading worryingly fast. The U.K. estimates that by 2015, the population of Botswana will be 31% smaller that it would have been in the absence of AIDS. In Sub-Saharan Africa, at the end of 2002, an estimated 50,000 people were on antiretrovirals, out of an estimated 4 million or so who need them [12]. Obviously the wealthier the country, there is more capability to control the disease and produce medicine.

Although D.C. has an AIDS rate that is 12 times higher than the national’s average, and increasing the availability of sterile syringe curtails transmission of HIV/AIDS, Congress last year renewed prohibitions on local funding for D.C.s clean needle exchange program. U.S. capitol is the only city in the country barred by federal law from using local tax money to finance needle exchange programs. It is also the city with the fastest growing number of new AIDS cases [13]. The DC appropriations Act have also been used as a vehicle to restrict syringe exchange. Virginia Senator George Allen, who sponsored the Senate amendment to the bill, commented, “Giving a drug addict a clean needle is like giving an alcoholic a clean flask. It just doesn’t make any sense” [14]. In 1988, Congress banned the use of federal money for needle exchange programs, though it included an exception allowing the president to waive the federal ban if a review from the surgeon general or the secretary of health and human services determined that syringe exchange programs had been proved effective and did not increase drug use. President Clinton did not remove the ban on syringe exchange financing, and in 1998 Congress reinforced the ban by removing the executive waiver [15].