Colgate University First Year Seminar 39: Earth Resources

Term papers

________________________________________________________

The Tragedy of Love Canal

Ryan Cole

December, 2000

Niagra Falls, New York is a medium sized community located in northern New York, and attracts a heavy tourist industry who come to view the splendor and beauteous spectacle of Niagra Falls. However, what they do not know is that less than twenty years ago, this tranquil suburb was under a severe medical state of emergency after an event referred to as the tragedy of Love Canal. At that time, deleterious chemicals from a shallow underground landfill leached up to the surface of a residential town and endangered the lives of all those who came into contact with the toxins. With major landfill cleanup only in its early stages of development, Love Canal residents literally fought for their lives to escape chemical poisoning by contaminants that the government could barely contain. Their pain and suffering has been documented in order to understand what happened to touch off the Love Canal incident. Looking back on the disaster, there is a great deal that can be learned and it is clear that this catastrophe should never have occurred and could have been avoided by a little common sense and communication on the part of both the town and its residents.

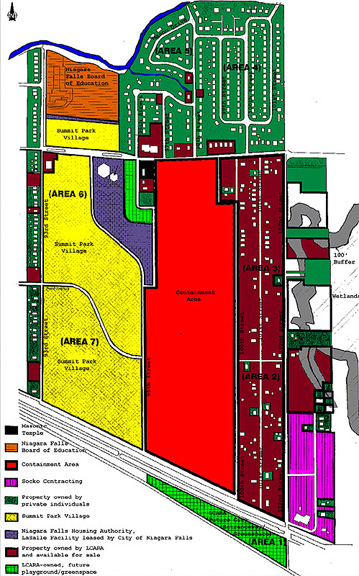

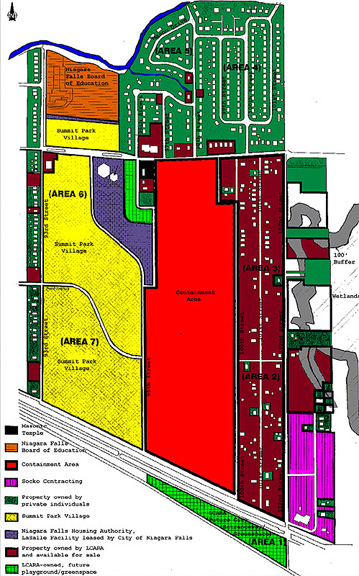

[Figure 1]

http://ublib.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal/lcmap.html

This map lays out the entire Love Canal region. Each of the color coded areas represent the different sectors of the area and give a brief description of what was located there during the time of the tragedy.

[Figure 2]

http://ublib.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal/background_gif/records/etta25.htm

This is a more in-depth and detailed map of the Love Canal region. Similar to figure 1, it also indicated what each of the regions represents and what was located there at the time of the accident.

The Love Canal refers to a neighborhood in the southeast LaSalle district in the town of Niagra Falls, New York and houses just over 70,000 residents (EPA fact sheet, 2000). The area gained its name from the late nineteenth century entrepreneur William T. Love. He had the idea of connecting a four mile passage beginning at Niagra Falls and leading to a river at the mouth of Lake Ontario so that ships could bypass the falls. This would be an ideal location to harness water and to generate power for the expanding industries developing along the seven mile stretch of river. However, a few years later his dream of the waterway faded primarily due to economic depression and a lack of financial backing, so the one mile and sixty feet wide canal already excavated was sold along with the surrounding land at a public auction in 1920. It was then turned into a municipal and chemical dumping site. From 1943 to 1952 Hooker Chemical, one of the many chemical plants located along the Niagra River, filled the canal with nearly 21,000 tons of toxic chemicals (Love Canal Collection, 1998). At the time, there were few regulations dealing with chemical disposal, so the Love Canal dumping was fully legal. Upon reaching maximum capacity in 1953, it was then layered with dirt and sold to the local board of education for a dollar with a disclaimer of responsibility for the land due to the presence of toxic chemicals. With this, Hooker Chemical was freed of all liability for consequences associated with the Love Canal and surrounding land. As the need for land increased, the town quickly expanded and used the area above the chemical disposal site to build housing and single-family residences. Among these was the 99th Street School, which was build directly on the former landfill. At the time, homeowners were not warned or provided information of potential hazards associated with locating close to the former landfill site. Within the next fifteen years up until the early seventies, there were numerous and repeated complaints filed by residents regarding unusual odors and substances emanating from their yards. In response to these allegations, Niagra Falls hired the Calspan Corporation to investigate and remedy the situation. "A report was filed indicating presence of toxic chemical residue in the air and in the sump pumps of residents living at the southern end of the canal. Also discovered were 50 gallon drums just below the surface of the canal cap and high levels of PCB’s (polychlorinated biphenyls) in the storm sewer system." (EPA fact sheet, 2000). Even as this report was being written and sent, more working class families moved onto the land directly above the contaminants. In April of 1978, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) began conducting their own studies to back the ones done five years earlier. This included air and soil samples from the basements of 239 homes immediately surrounding the canal zone. By April 25, 1978 Dr. Robert Whalen of the New York State Commission of Health had issued a local public health hazard warning for the communities surrounding the Love Canal. The area was immediately closed off and exposed barrels of chemicals were removed from the area. As concern grew by the townspeople about lingering toxic conditions and health concerns, the site was once again evaluated for its safety. However, in the late summer months of the same year, the canal had repeatedly failed inspections by various health departments and on August second Dr. Whalen declared a medical state of emergency at Love Canal and ordered the immediate closure of the 99th Street School. Immediate cleanup tactics were devised and put into use while those with compromised immune systems such as pregnant women and children under the age of two were hastily relocated to homes outside the designated hot zone since they are the most susceptible to chemical poisoning. Some of the first tactics centered on the layout of Love Canal and the extent in which the chemicals have spread since they were first introduced into the environment in the early forties. Although crude strategies, they had enough impetus to carry the entire cleanup during the beginning few weeks. Less than five days later President Jimmy Carter declared the Love Canal a federal emergency and allocated funds to permanently move the 239 families living in homes directly above the landfill. However, the disaster was far from over.

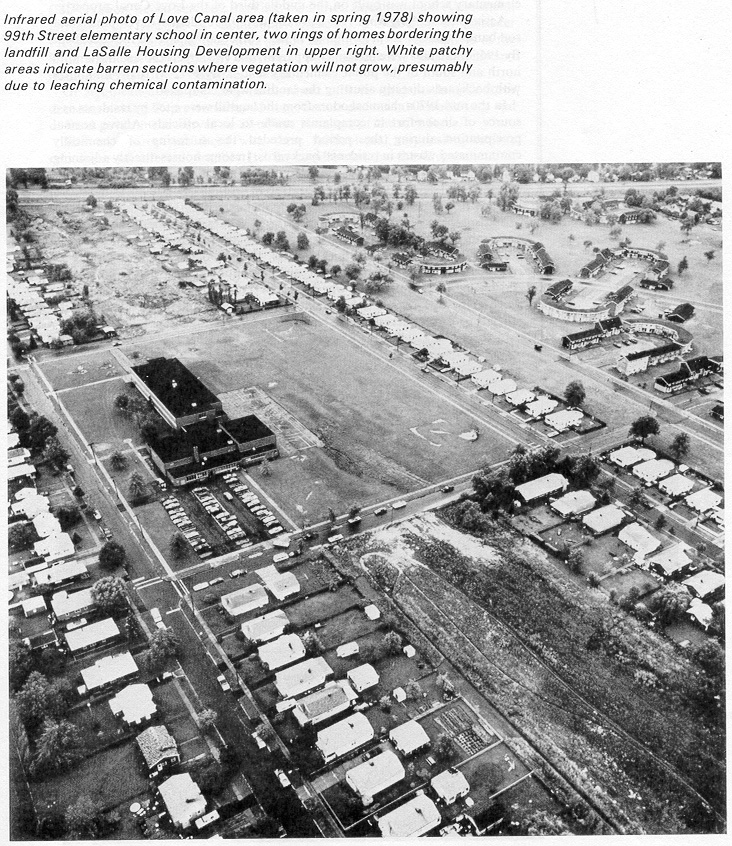

[Figure 3]

http://ublib.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal/aerial_photos/aerial_etf.htm

This figure shows a portion of the housing and municipal buildings in the damage zone at Love Canal. In the upper left corner is the LaSalle Housing Development, which is located to the West of the canal proper.

[Figure 4]

http://ublib.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal/aerial_photos/aerial_1980.htm

This picture gives a clear view of the Love Canal area. The canal itself is in the center of the picture and gives an unobstructed view of the southern end.

Although Hooker Chemical dumped a multitude of chemicals into Love Canal, the ones discarded in the largest quantity were PCB’s. These encompass a class of chlorinated compounds that include up to 209 variations, or congeners, with different physical and chemical characteristics (Gascape PCB Index, 1997) and simply consist of chlorine, carbon, and hydrogen. Most PCB’s are oily liquids whose color darkens and viscosity increases with rising chlorine content. Many industries use PCB’s in a wide range of industrial and consumer products. Some of these properties include its very stable nature, low volatility at normal temperatures, relative fire-resistant make-up, and absence of conductability. PCB mixtures are usually light-colored viscous liquids that are soluble in organic solvents but very insoluble in water. This makes it such that if a PCB mixture enters water, it will sink to the bottom. They were commonly used in the electrical industry for a safer cooling and insulating fluid for industrial transformers and capacitors. (FAQ about PCB’s, 1997).

Due to the lack of information regarding PCB’s and their detriments to the environment, they have been routinely disposed of over the years through open burnings or incomplete incineration. However, the main source of PCB pollution comes from "direct entry or leakage into sewers and streams as well as dumping into non-secure landfill sites and municipal disposal facilities." (Love Canal Collection, 1998). Ironically, their chemical stability useful in industrial applications couples with its tendency to accumulate in living tissue means that PCB’s are stored and concentrated in the environment and is classified as bioaccumulation. In the case of the Love Canal, the rise in the water table as a result of the added toxins brought contaminated groundwater to the surface and entered the Niagra River. Also, runoff drained into the river only three miles upstream from the municipal water treatment plant and contaminants entering existing sewers from the landfill were quickly deposited into nearby creeks. This is particularly worrisome since the Niagra Falls treatment plant serves 77,000 people.

Following the declaration of a federal emergency by President Jimmy Carter, the focus quickly shifted to health concerns for those who were directly exposed to the chemicals. By 1972, scientific evidence suggested that PCB’s posed a serious potential hazard to human health. Because of the stability of PCB’s, many exposure routes must be considered; dermal exposure, ingestion of PCB contaminated soil, water and food; and inhalation of ambient air contaminated with PCBs. (PCB Index, 1997). Traces of PCB can be found in virtually every living organism, including humans. However, there have not been any conclusive links to determine the full health effects on humans. The most commonly observed health effect from extensive exposure to PCB’s is chloracne, a painful and disfiguring skin condition, similar to adolescent acne. Liver damage is also possible. (FAQs about PCB’s, 1997). Other than these long-term conditions, people exposed in the short-term may suffer from rashes, aches in their joints, eye irritation, or a light burning in the glands.

[Figure 5]

http://ublib.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal/aerial_photos/aerial_1980.htm

This picture offers a view of the southern portion of the Canal. At the bottom is the LaSalle expressway.

[Figure 6]

http://ublib.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal/aerial_photos/aerial_1980.htm

This figure shows the 93rd street school with surrounding housing developments around it. This area was directly over the chemicals dumped by Hooker Chemical.

[Figure 7]

http://ublib.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal/aerial_photos/aerial_1980.htm

The next figure is a photograph of the LaSalle Housing Development, which was demolished in 1983.

Once the extent of the disaster was realized, officials and government representatives then had the task of cleaning up more than 20,000 tons of leaking chemicals. In order to break down the immense task, it was divided into seven stages; three that focused on the initial problem and the remaining four concerned with the long-term effects of Love Canal. The first was merely initial reactions by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC). They began by installing a system to collect leachate from the site and led to the construction of a leachate treatment plant, along with the covering and fencing of the entire landfill area in 1981. Upon completion, in 1982 the EPA erected a barrier drain and a leachate collection system in order to prevent any precipitation from coming into contact with the buried wastes. This made it difficult for the chemicals to enter the aquifer and groundwater within the Niagra region. The next three years were primarily used to demolish contaminated houses adjacent to the landfill and nearby school, as well as conduct studies to determine the best way to proceed with further site cleanup. (EPA Fact Sheet, 2000). In May of 1985, the EPA then focused its attention on the sewers and creeks neighboring the landfill. Sewers were inspected for defects that could allow contaminants to migrate and then a total of 68,000 linear feet of piping was hydraulically cleaned. This freed up all of the contaminated sediments and washed them to a concentrated area where they could be removed. In 1989, 14,000 cubic yards of sediment were dredged from Black and Bergholtz creeks alone from a total of 33,500 cubic yards. Grass was then replanted along the banks and clean riprap was placed in the creek beds. (EPA Fact Sheet, 2000). While this was being completed, in October 1987 the EPA constructed an onsite facility to dewater the sediments and treat them through thermal destruction. In total, these beginning measures greatly reduced nearly all of the chemicals in a three mile radius of the dumping site.

Although the short-term actions taken were remarkably efficient, long-term planning was necessary to stabilize the landfill area. As areas near the landfill were remedied and treated, all remaining questions unassociated with health focused on environmental damage. With the sewer systems clean and no new toxins flowing into the groundwater, the EPA was fairly confident that the pollution had been controlled and the situation could only get better. Beginning in June 1990, annual or semi-annual checks were preformed to monitor the contaminant levels in Love Canal and also to determine whether the chemicals were spreading. The dioxin and PCB concentrations had leveled off and the hot zone had ceased to grow. In December 1998, a "10 ppb treatability variance for dioxin for the stored Love Canal waste materials" (EPA fact sheet, 2000) was established and the remaining sediment and waste materials collected were subsequently shipped off for final disposal in March 2000.

Overall, Love Canal was a disastrous event in American history and will be remembered well into the future. It was one of the worst environmental tragedies ever and prompted a federal emergency that left thousands of people without homes and fearing for their lives. As of present day, Love Canal is still being monitored closely with positive results coming from sustained pollutant levels. Thinking back logically, this event should never have occurred. Without moral lapses on the parts of Hooker Chemical and the local board of education, the proceeding string of events could have been avoided Although Hooker Chemical may have been unaware of the full extent of hazards caused by PCB’s, it is certain that they knew the chemicals were somewhat deleterious. Ultimately, it is society’s incessant urge to grow and expand with little thought going toward environmental damages and reactions. There is a fine line separating the balance between man and nature and their mutual destruction, and we need to know when we have gone too far and are damaging the environment. The Love Canal tragedy was not singly about poor chemical and housing decisions, but also how the Niagra community crossed that line.

References Cited

Craig, James R., Vaughan, David J., Skinner, Brian J. Resources of the Earth. Prentice Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ; 2nd ed., pgs 59,80, 249, 456: 1996.

Eufemia, Nancy A. "A Biochemical Response to Sediment- Associated Contaminants in Brown Bullhead From the Niagra River Ecosystem." Klower Academic Publishers. Ecotoxicology 6, journal no. 1 (1997): pgs. 13-35.

http://ublib.buffalo.edu/libraries/projects/lovecanal. Love Canal Collection. State University of New York at Buffalo; 1998.

http://www.epa.gov/region02/superfnd/site_sum/0201290c.htm. EPA Site Fact Sheet. Environmental Protection Agency; June 13, 2000.

http://www.gascape.org/index%20/PCB%20index.html General PCB webpage. Gascape Organization, 1997.

http://gascape.org/index%20FAQs_About_PCBs%20.html Commonly asked questions about PCBs. Gascape Organization, 1997.

Jones, Jack. "Link Between Canal Chemicals, Illnesses May Never Be Proven." Niagra Gazette. June 8, 1980.

Levine, Adeline. Love Canal: Science, Politics, and People. Lexington Books: Lexington, MA; 1982.

Ploughman, Penelope. "Disasters, the Media, and Social Structures: Persistence Based on Newspaper Coverage of the Love Canal and Six Other Disasters." Blackwell Publishers. Disasters 21, journal no. 2 (1997): pgs. 118-138.

Tyson, Rae. "A Year Later, Canal Homes Sit in Silence." Niagra Gazette. May 17, 1981.

Tyson, Rae. "Canal Tragedy Not Yet Over." Niagra Gazette. May 3, 1981.