|

An Indebted Israel Shelters a Kosova Family (NY Times)

http://www.alb-net.com/kcc/050399e.htm

By JOEL GREENBERG

MAAGAN MIKHAEL,

Israel

-- When Lamija Jaha and her husband were driven out of their apartment and

herded with thousands of ethnic Albanians to trains that would take them

from Pristina, the capital of Kosova, she took a memento of her dead father

in her pocket.

Trudging into exile on that first day of April, she had no idea that the

simple souvenir from her lost home -- a copy of a certificate bearing her

father's name -- would help pluck her family from the Balkan flames and

bring it to this kibbutz on the northern Israeli coast.

That piece of paper would take the Jaha family, in a way, full circle. It

was the copy of a certificate, issued by the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial

in Jerusalem, commending her parents, Dervis and Servet Korkut, both

Muslims, for risking their lives to save Jews during World War II, and

honoring them as "righteous among the nations."

In World War II, Mrs. Jaha's parents lived in Nazi-controlled Sarajevo,

where she was later born and her mother remains today. Not only did the

Korkuts hide several Jews from the local pro-Nazi regime, but Dervis Korkut

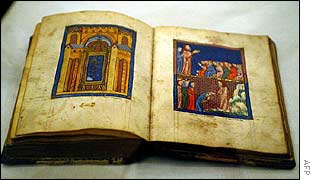

saved the precious Sarajevo Haggadah, concealing it in his home and thus

keeping the 14th-century volume, the best known illuminated Hebrew

manuscript, intact.

Now it was Mrs. Jaha who was expelled from her Kosova home and herded onto a

crowded train in scenes that have evoked comparisons with the Holocaust.

After arriving in

Macedonia,

Mrs. Jaha showed her father's commendation to officials of the Jewish

community in the capital, Skopje.

They helped Mrs. Jaha and her husband, Vllaznim, to join a planeload of

Kosovar Albanian refugees accepted by Israel.

More than 50 years after her parents sheltered Jews in their home, she found

shelter in the Jewish state.

"I don't know how to express how much this means to me," Mrs. Jaha, 44, said

in an interview at a hostel in Maagan Mikhael, where the 115 refugees are

being housed. "My father did what he did with all his heart, not to get

anything in return. Fifty years later, it returns somehow. It's a kind of a

circle."

Mrs. Jaha's father was a museum curator and a prominent figure in Sarajevo,

an expert on the ethnic history of Bosnia-Herzegovina who knew several

languages and took a special interest in Jewish contributions to the

cultural mosaic of his country. In published articles, he wrote about the

culture and art of Bosnia's Jews, defending them against anti-Semitic

attacks and asserting that they were an integral part of Bosnian society.

As thousands of Jews were rounded up and shipped off to concentration camps,

Korkut took the deadly risk of hiding several in his home. Mira Bakovic, a

Jewish survivor who was traced by Yad Vashem, recalled that the Korkuts put

her up for half a year after she sneaked back to Sarajevo following a stint

as an anti-Nazi partisan fighter.

She was was presented to visitors as a housemaid with the Muslim name Amira

and served guests, including German officers, veiled according to Muslim

custom.

Mira Bakovic died last year at age 76, but her son, Davor Bakovic, 50, who

immigrated to Israel

from Yugoslavia in 1970 and lives near Jerusalem, greeted Mrs. Jaha when she

and her husband arrived at

Ben-Gurion

Airport on April 12.

"It was an amazing discovery," Bakovic recalled. "I felt as if a sister had

appeared from a faraway place. I felt close to these people even though I

didn't know them at all. The circle of my life had become linked with Lamija

and her family. To me it proved that people can't be divided up into nations

and sects. They're human beings who can touch each other."

The meeting was also a revelation for Mrs. Jaha. She said that her father,

who died when she was 14, never mentioned to her that he had sheltered Jews,

and that her mother told her briefly about it only a few years ago. "My

father didn't do it so he could tell us about it later," Mrs. Jaha said. But

in the end, "anything my father did brought me good."

For the Jahas,

Israel

is a new beginning after days of hell.

In the crush at the Pristina train station, they climbed through a window to

get into a packed passenger car. Two bags in which they had tucked mementos

of their life -- family photos, a picture of Korkut, his books, a daughter's

diary -- were lost in the chaos.

Dumped on the Macedonian border in darkness, the Jahas marched along the

tracks into a teeming no man's land where they spent 11 hours before gaining

entry with a small group of refugees at a Macedonian checkpoint.

After an unsuccessful attempt to get permission to go to Sweden, where her

brother-in-law lives, Mrs. Jaha went to the offices of the Jewish community

in Skopje and showed the certificate awarded to her parents. A few years

ago, her mother had been evacuated from Sarajevo in a convoy organized by

Jews there during the Bosnian war, and Mrs. Jaha hoped she might get similar

help. The president of the Jewish community in Skopje, Victor Mizrahi,

promised help.

Asked whether she was willing to go to Israel on a refugee flight organized

by the Jewish Agency, an organization that usually brings Jewish immigrants

to Israel, Mrs. Jaha readily agreed.

"I told them that it was no problem, and that we wanted to go somewhere

safe," she recalled, noting that she was unconcerned by the occasional

outbreaks of Arab-Israeli violence. "The problems here are nothing compared

to the situation in Kosova. You can find terrorism all over the world."

The Jahas' two children, Fitore, 20, and Fatos, 16, were smuggled out under

false Serbian identity to

Belgrade

and later to Budapest before their parents' expulsion.

They were brought to Israel on a separate Jewish Agency flight that carried

Serbian Jewish youngsters who had fled the NATO air attacks to

Hungary.

Reunited in Maagan Mikhael, living in white stucco guest rooms overlooking

the kibbutz's fish ponds and the

Mediterranean, the Jahas feel "like we're on vacation, not

refugees," Jaha said. The Jewish Agency has provided Hebrew classes and

lectures for the refugees, sightseeing trips, three meals a day and medical

care. There are also plans to start employing the newcomers at the kibbutz

and in neighboring industries.

Many of the refugees, who have been accepted by

Israel for six months,

say they would like to return to Kosova, but the Jahas say they have

resolved to settle in Israel.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu personally assured Mrs. Jaha that her

family can stay, and in recognition of her parents' deeds, the family is

eligible for Israeli citizenship.

"This was a big thing for us, because we have no home, we have nothing, and

we've come to a country that won't turn us back," said Mrs. Jaha.

"We have left our house for good. We wanted to go far away, where we and our

children could live without war."

Mrs. Jaha, an economist, and her husband, an electrical engineer, say they

plan to find work and permanent housing after learning Hebrew, and their

daughter, a college student, is determined to resume her computer studies at

an Israeli university.

"We're doing this for the children, not for us," Jaha said of the decision

to stay in Israel. "We lived one life. Now we're beginning another."

-----------------------------

What goes around, comes around

One family finds

freedom a generation after their ancestors defended it

By Cynthia Cannon

Princeton Packet Staff Writer

Wednesday, July 26, 2000

|

|

|

|

Neither fire nor wind,

birth nor death can erase our good deeds.

The profound words of the Buddha still ring true — many believe good

deeds never go unnoticed.

But sometimes it takes a while.

More than 50 years ago, in Nazi-controlled Sarajevo, Dervis and Servet

Korkut, both Muslims, risked their lives to save Jews during World War II.

But it wasn't until 1999 that the Korkuts' benevolence was returned. Last

April, a memento from World War II honoring the Korkuts for their good deed

saved the lives of their daughter, son-in-law and grandchildren.

Unfortunately, Mr. Korkut did not live to witness the gifts his family

reaped because of his kindness.

This is the story that both a cheerful and teary-eyed Fitore Jaha, the

Korkuts' granddaughter, shared with more than 85 guests at Thursday

evening's event, "From Kosovo to Israel — A Bridge to Peace." held at The

Center for Jewish Life in Princeton. The event was sponsored by the Young

Women's Group of the Princeton Chapter of Hadassah.

The 21-year-old Ms. Jaha was driven out of Kosovo, along with her family

and other Kosovar Albanian refugees, when their homeland was at war with the

Serbs in March 1999. Israel was the only country offering the refugees a

place to live.

Once in Israel, Hadassah played a key role in transforming the Jahas'

difficult life — particularly, Ms. Jaha's — into one of security and

opportunity.

Mr. Korkut, Ms. Jaha's maternal grandfather, was a museum curator and an

expert on the ethnic history of Bosnia-Herzegovina, she said, unfolding her

inspiring story. During the Holocaust, he published articles in which he

defended Bosnian Jews against anti-Semitic attacks. When Jews were being

sent to concentration camps, Mr. Korkut hid several of them in his home. He

also salvaged a rare 14th century volume of the Hebrew manuscript, "Sarajevo

Haggadah," saving it in his home.

After the war, the Korkuts were issued a certificate by the Yad Vashem

Holocaust memorial, commending them for risking their lives to save Jews.

The certificate names its recipients "righteous among nations," Ms. Jaha

translated.

Later, a copy of the treasured certificate bearing Mr. Korkut's name was

kept in a safe place by Lamija and Vllaznim Jaha, the Korkuts' daughter and

son-in-law. The couple didn't know at the time how valuable it would be

until last spring.

Fitore Jaha, then 20, was immersed in her studies when she began to hear

the first sounds of NATO's bombing ring through her hometown the evening of

March 24, 1999. She was a student at the University of Pristina at the time.

Her brother, Fatos, then 15, was at home, enjoying a good time with high

school friends.

"We heard the Serbs were wearing masks, looting and bombing shops in the

city and firing guns," recalls Ms. Jaha. "We were frightened and could not

leave our apartment for five days straight."

On March 29, Ms. Jaha and Fatos were smuggled out under false Serbian

identity to Belgrade and later to Budapest.

"The hardest thing in the world was to leave my parents behind," she

admitted. "I had this crazy notion that the war would be over in 10 days,

but I learned I was wrong when 10 days passed and we still didn't hear from

my family."

Meanwhile, Mr. and Mrs. Jaha were expelled from their Kosovo apartment

and transported to the Pristina train station in the middle of the night.

They climbed through the train's window, with only a few belongings.

The Jahas lost beloved photos and documents along the dangerous journey.

"I only wish my father had taken my CDs with him," Ms. Jaha confessed. "I'm

really into grunge rock and American musicians."

The train transported Mr. and Mrs. Jaha to a Macedonian checkpoint. They

attempted to get to Sweden, where Mrs. Jaha's brother-in-law lives. After an

unsuccessful attempt to enter Sweden, Ms. Jaha had her father's Yad Vashem

Holocaust memorial certificate in hand and proudly carried it to the offices

of the Jewish community in Skopje.

The Jewish community president, Victor Mizrahi, agreed to help.

The Jahas were passengers on a refugee flight to Israel organized by the

agency. Shortly after, the Jaha children were brought to Israel on a

separate Jewish Agency flight that carried Serbian Jewish children who had

fled the NATO air attacks to Hungary.

The Jewish Agency provided homes to the refugees. The Jahas reunited with

their children April 15, 1999, within the kibbutz they would live in

overlooking the Mediterranean Sea.

"I cannot explain…the joy I felt…at seeing my parents, it was the

happiest day of my life," explained Ms. Jaha, overwhelmed with feeling. The

Jewish Agency also provided Hebrew classes, sightseeing trips, food and

medical care for the refugees.

The Jahas were assured of their eligibility for Israeli citizenship by

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Ms. Jaha's parents were previously employed as an electrical engineer and

economist. Currently, they are employed in a factory in the city of Maagan

Mikhael. Language barriers have kept them from continuing in the careers

they enjoyed in Kosovo.

In the kibbutz, Ms. Jaha was disappointed because her college education

was interrupted. Her brother was continuing high school in Israel.

When at the university of Pristina, she had been in a computer design

program. All her life she enjoyed drawing; she was attending courses in

graphic design, computer engineering and animation. "When I first went to

Israel, my future was uncertain."

On Sunday, May 2, 1999, a member of Hadassah was reading the Sunday New

York Times in her New Jersey home. She read Joel Greenberg's story, "Crisis

in the Balkans: Refugees — An Indebted Israel Shelters Family of Kosovo

Albanians."

The article said: "That piece of paper (the certificate issued to Mr.

Korkut) would take the Yaha family, in a way, full circle…. More than 50

years after her parents sheltered Jews in their home, she found shelter in

the Jewish state."

Mr. Greenberg quotes Mrs. Jaha: "My father did what he did with all his

heart, not to get anything in return, 50 years later it returns somehow.

It's kind of a circle."

The anonymous reader was so moved by the Jahas's story, said Kim Wishnow-Per,

president of the Young Women's Group of the Princeton Chapter of Hadassah,

she contacted the Princeton group and asked how Hadassah could provide more

help to the family.

Hadassah agreed to pay Ms. Jaha's tuition and expenses as she continues

her education in computer design at Hadassah College of Technology.

Ms. Jaha resides in a dormitory at HCT in Jerusalem, a two-hour drive

from her parents and brother who now live just outside the kibbutz.

"I'm very focused on my studies. My lectures are taught in Hebrew, but

I'm picking-up the language pretty quickly," Ms. Jaha admitted. "I'm

grateful, though, that my textbooks are printed in English."

"My life has changed so much in the past year. When I was in Kosovo, my

point of view was so pessimistic about almost everything. But now I think

there are lots of good people that accomplish great things in the world,"

Ms. Jaha emphasized. "I'm much happier too that the war is ended."

The Jahas have decided that they will make Israel their home.

Ms. Jaha is enthusiastic about an August trip she has planned to Kosovo.

"I've missed family and friends. Thank goodness there's e-mail to keep in

contact with them," Ms. Jaha said. "I also plan to retrieve the rest of my

CDs."

Hadassah is the largest women's and largest Jewish organization in the

United States. In the U.S. it

promotes women's health education and research, community volunteerism,

social action and advocacy, partnerships with Israel, and the Young Judaea

youth program. Founded in 1997, the Young Women's Group of the Princeton Chapter of Hadassah is the fund-raising arm of the international

Hadassah group. For more information about the Young Women's Group, call Ms.

Wishnow-Per at ((609) 683-1911, ext. 205.

|