![]()

What Can Be Done?

Being an epicenter of the spread of AIDS, the Bronx proves to be one of the most difficult areas to advance in prevention efforts. In the previous sections, various data was collected and analyzed. The noticeable correlations with AIDS rates were income status, minority status, education, and immigration. Of these four, minority status and education are the place to start for getting something done, although the other two do factor into the issue. They both show strong correlations and less complication for finding solutions. Another area that was not explored in the previous paper is young Latino MSM. Here, young is defined between the ages of 15 and 22. (Agronick, pg. 185) Of all the Latino YMSM in New York City, 9% have positively tested for HIV. (Agronick, pg. 185) In order to make the largest difference and prevent as many cases as possible, it is imperative that these groups get the most attention.

In 2004, 90,298 New Yorkers were living with HIV/ AIDS and that number is expected to increase by 10,000-30,000 within the next three years. (Shedlin) With Hispanics accounting for 31.9 % of these cases (Shedlin), the Bronx looks to be hit the hardest by the increase in AIDS rates. Clearly, despite past prevention efforts, the citizens of the Bronx are not getting the message. More money and time needs to be focused towards prevention efforts in the Bronx.

Even though its area is small, 1.3 million people have managed to make their homes in the Bronx and the population is only growing. This makes prevention increasingly difficult. The best way to attack this problem is to hit the areas with the highest AIDS rates. By zip code, these areas include 10451, 10452, 10454, 10455, 10456, 10457, 10459, 10460, 10474, and my hometown in 10453. When looking at a map of the Bronx, these area codes all fall into the area that has been dubbed “the south Bronx”.

The biggest problem is that people in this area are not exposed to the facts and the message of prevention. Three problems contribute to this lack of exposure: one is poverty, the second is the Hispanic culture, and the third is education. First, most Bronx residents are too poor to make time to get involved in community events. Either they do not have the money to travel or they cannot take time off work because less work equals less money to support themselves and their families. Second, the Hispanic culture forbids discussing certain matters, such as homosexuality and AIDS, because it is immoral and wrong. Many stigmas and personal issues lie behind Hispanics’ hesitation to seek help or talk about AIDS. The third starts in the place where such an important health issue should be discussed: school. Many schools simply leave out AIDS from the curriculum. If there were ways to improve these problems then it is likely that prevention efforts can be noticed and AIDS rates in this area could drop. Another problem is that AIDS awareness is far too low. According to one report, even though Latinos are in dire need of AIDS education, they get overlooked because many think that AIDS is talked about too much and that the public knows enough. (Addressing HIV/AIDS, pg.25) This is a startling report because the increasing AIDS rates show that Latinos are not getting the information, so something needs to be done.

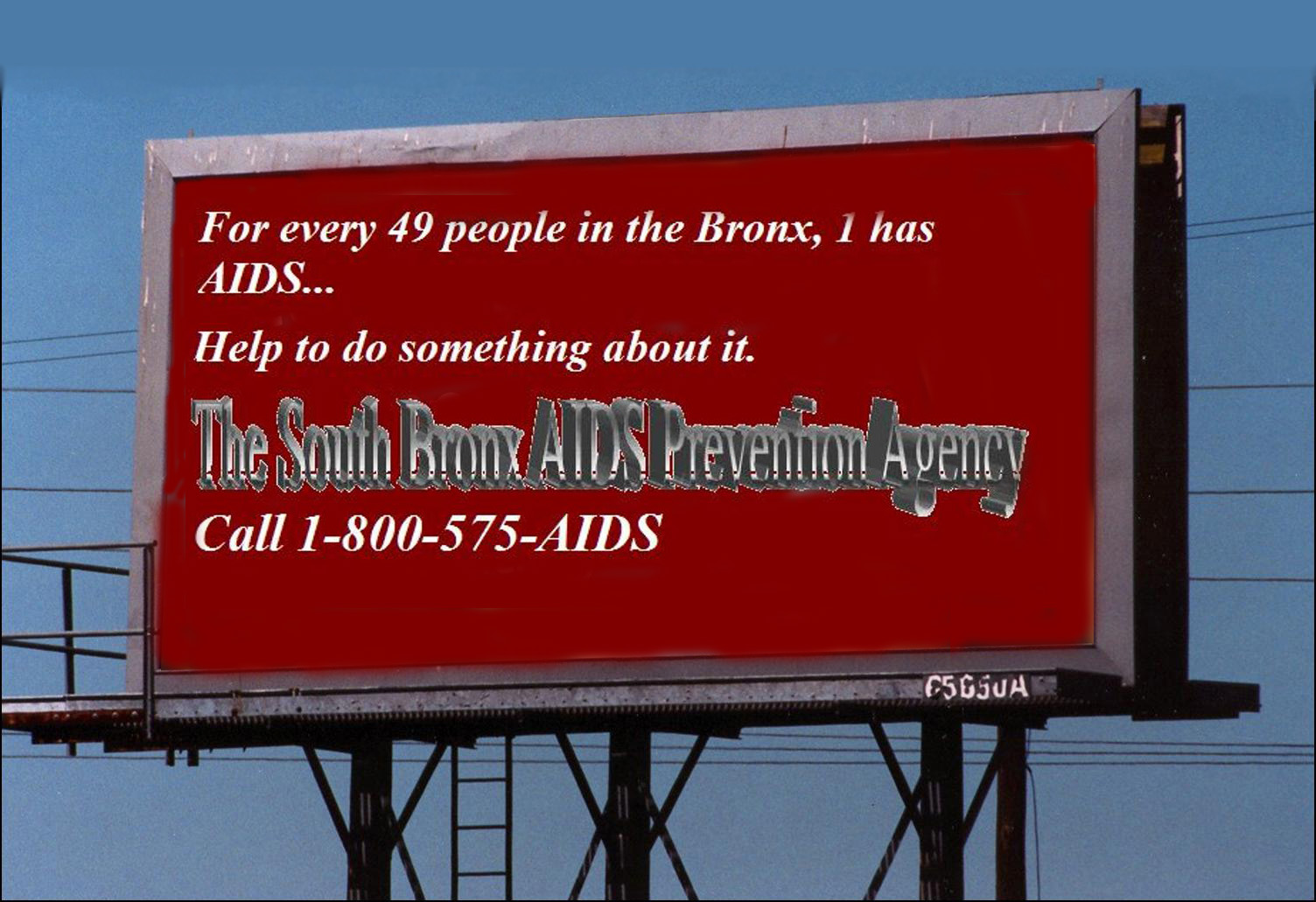

Before addressing the problems previously mentioned, a plan for prevention should be generally laid out and then refined based on those three obstacles. One of the most effective methods of prevention is a group session/meeting. In such a program, which we will call The South Bronx AIDS Prevention Agency; those who attend can learn about all of the risk behaviors and safety measures they can use to avoid getting AIDS as well as other diseases. One study showed that most Hispanics, particularly the new immigrants, did not possess sufficient knowledge concerning AIDS (Shedlin pg.53). Besides knowing that it is a disease, many Hispanics said they knew how one got AIDS. (Shedlin pg.53) They said it was dependent on whether they “knew” their partner, basically if they had trust in their partner. (Shedlin pg.53) Many were unaware of the seriousness of the AIDS epidemic and most did not even know how to identify the symptoms. (Shedlin pg.54) Without being equipped with this knowledge, how can anyone expect Hispanics to combat AIDS? Many of these Hispanics were not even aware of the risks they were already taking. (Shedlin pg.54) Since poverty is an increasing problem, more Hispanic women find themselves resorting to prostitution. (Shedlin pg. 54) Perhaps if those who were participating in the risky behaviors knew what they were putting on the line then they could make an educated decision based on all the facts. In order to correct this dilemma, the proposed information sessions must include sufficient facts so that every participant is knowledgeable enough about AIDS. They need to know every possible consequence. In addition, the sessions can possibly provide some alternative methods to relieve financial stress. For those that participate in risky behavior for reasons other than money, counseling can be offered to assist in ending the risky behavior.

Part of the risky behavior is that partners are not notifying each other about their health status. With a partner notification program in place, perhaps safer practices can begin to help avoid spreading AIDS even more. Such a program takes a lot more work and comes secondary to the main program.

In order to accommodate inevitable problems when trying to implement a group information session for Hispanics, the original and general plan must be refined. It must be taken into consideration that on average, 42.93% of Hispanics in the south Bronx live below the poverty line. Their financial struggles inhibit them from making the time to attend. To offset this, the program can offer monetary incentives ranging anywhere from $20-$40, depending on the budget for the program. In addition, transportation can be offered in the form of bus/train fare.

The minority status of Hispanics also plays a large role in the process of forming these programs. Being Hispanic can pose difficulties in having an effective meeting. First, anyone who speaks at the meeting must be bilingual so that there is no language barrier. All documents must be made bilingual as well. However, straight translations are not the way to go. Many words like gay or gay pride do not exist in the Spanish language so slang terms have been given to identify these ideas. (Carballo-Dieguez) Speakers should have knowledge of these slang terms so that effective communication takes place. Many Hispanics in this area are illegal immigrants who fear being deported. This leads to their hesitation to seek help for problems. A key part of these sessions is confidentiality. All information must stay between the speaker/moderator/counselor and the participant.

One of the biggest issues when discussing prevention efforts for Latinos is the family. Hispanic culture and family values play major roles when it comes to AIDS. This is a particularly difficult struggle when the male is homosexual. Such strong family bonds act as a double-edged sword in that there may be a family member willing to offer support, but the family can also be very adamant about learning the information of another family member and ultimately spreading it, which is exactly what the person does not want. However, we can play off the closeness of families to help convince participants to “come out”. Since families are so close and care so much, they should be very concerned with the health status of one of the family members. Telling the family can have more benefits than negative consequences because close families are more ready and willing to help and support. Emphasizing the pros over the cons of telling the family can help participants overcome their fear and tell their family. Since most Hispanics are catholic, being homosexual is looked down on, so a male who is homosexual may encounter insurmountable pressure from the family to change and may even be ostracized by the family. Fear of this leads most gay Hispanics to keep their identity a secret. One case study had a gay Hispanic male who had a male partner for twelve years, but kept it from his family. (Carballo-Dieguez) When they questioned his single status he simply replied that he hadn’t found the right woman. (Carballo-Dieguez) Responding to this, the family tried to set him up with numerous women, which caused him to have anxiety attacks. (Carballo-Dieguez) Cases like this need to be handled carefully. Counseling can help the participant find ways to cope or find ways to come clean to the family. Another study details the desire to disclose information. This study was made to test stigma and social barriers to medication adherence in HIV/AIDS patients. (Rao) Results in this study show that many participants preferred to keep the fact that they had HIV/AIDS to themselves. (Rao) One participant described a situation where if their family knew, the information would spread quickly because it is big news, and that made her nervous. (Rao) Although this study had an alternate purpose, it does show that AIDS patients will do whatever they can to keep their condition a secret, even with their sexual partners. This compromises prevention efforts, so the group sessions must address this as well and advise participants the danger in withholding such information.

Another major issue is condom use. Obviously, a lack of condom use greatly increases the chances of contracting AIDS. A large part of these information sessions must include the use of condoms because many men in the Bronx do not use condoms. One study illustrates the lack of condom use. This study included 182 Puerto Rican men in New York City. (Carballo-Dieguez, Alex, and Curtis Dolezal) Each man was interviewed to determine the extent of unprotected sex, the number of men who reported having AIDS, seroprevalence, obstacles, benefits and reasons for condom use, and the effects of culture on the reported obstacles over the previous year. (Carballo-Dieguez, Alex, and Curtis Dolezal) Results show that 45% of the respondents who had anal sex did not use a condom or used one sometimes. (Carballo-Dieguez, Alex, and Curtis Dolezal) The main reasons for not using condoms included: dislike of condoms, some thought their risk levels were low, they trusted their partner enough that they did not use a condom, condoms were not available, lack of control, and indifference/ignorance about condoms. (Carballo-Dieguez, Alex, and Curtis Dolezal) The program should address every “obstacle”, because when looked at carefully, theses obstacles are nothing more than poor excuses for not practices safe sex, especially when the health status of the partner is unknown. In addition, Ninety percent of the interviewees knew that condoms helped prevent illness. (Carballo-Dieguez, Alex, and Curtis Dolezal) That may be the most startling result because it shows that they know the benefits, yet they still do not use condoms. The best way to counteract that is hand out free condoms and couple that with the most frightening, yet true, information about the consequences of AIDS and other illnesses. It is time to be blunt and straightforward with the information because scaring could be a very useful tactic in prevention efforts. Most group/information sessions already in place sugarcoat the truth because it’s easier for people to hear without scaring them away, but what the people need to hear are the cold hard facts so that they can know the repercussions of their actions.

We may encounter even more barriers in this prevention process. Some of these barriers are outlined in a report titled ‘The Sate of Latinos in HIV Prevention: Community Planning”. (The State of Latinos in HIV Prevention) It would be effective if we enlisted the support of trusted community leaders because this report shows that many Latinos do not trust programs like the one being proposed. (The State of Latinos in HIV Prevention) Many Latinos have had bad experiences with government agencies (The State of Latinos in HIV Prevention), so they might avoid programs like this one. Also, many programs do not acknowledge the stigma related with AIDS and homosexuality in the Hispanic community. (The State of Latinos in HIV Prevention) However, this program will address those stigmas and do everything possible to combat them with professional counseling and information. We must also document the results of our efforts by giving the participants updated AIDS data. According to the report, many Latinos avoid these programs because they see no results. (The State of Latinos in HIV Prevention) We must also stress that this is for the good of the participants because the report mentions that many Latinos believe these programs only have their own interests in mind. (The State of Latinos in HIV Prevention)

Most programs have trouble being successful because they do not have sufficient funds to make their programs work. This program will need many donations and other sources of financial assistance to carry out all of the plans. According to the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors, the Center for Disease Control only spends $1,474 per AIDS case in New York. (Addressing HIV/AIDS, pg. 23) Among the states with the highest AIDS rates, this is the second lowest even though this large city has many AIDS cases. (Addressing HIV/AIDS, pg.23) The 2003-2004 New York State budget included nearly six millions dollars intended for the AIDS community. (New York State HIV/AIDS POLICY ANALYSIS AND ADVOCACY) This money is split for both prevention programs and treatment programs. (New York State HIV/AIDS POLICY ANALYSIS AND ADVOCACY) However, another program, The AIDS Drug Assistance Program, received 96 million dollars. (New York State HIV/AIDS POLICY ANALYSIS AND ADVOCACY) While this program is a noble one and provides great medical services to those living with HIV/AIDS (New York State Department of Health), it does not address the spread of AIDS. In order to bring relief to the ever-rising AIDS rates in the Bronx, a prevention program needs sufficient funding to work because too many funds are going to treatment, which really does not solve the problem of the epidemic.

Another issue also deals with the government. As a public health official, it is only fitting that we rally to get help from the government. First, there needs to be more time spent in schools talking about AIDS and other health issues. More specifically, the content of these classes should be refined. According to the New York State Education Department, “Using accurate HIV-related terminology and HIV/AIDS information, the teacher will help to establish an awareness of the need for research at the State and Federal level for HIV/AIDS.” (New York State Education Department) Nowhere in that document does it say students should understand the specific health risks and specific safe practices they can use. Students focus more on rallying for AIDS research than on how to prevent AIDS from spreading, which is the more important issue. Second, health resources need to be more readily available to the poor community. The RWCA (Ryan White CARE Act) is a great example of one such service. (The AIDS Institute-Recommendations) One report calls for some upgrades and changes to the act to help prevention efforts and allow for better spending of the funds. (The AIDS Institute-Recommendations) In addition, there is a shortage of HIV/AIDS specialists (The AIDS Institute-Recommendations) and without those people, programs like The South Bronx AIDS Prevention Agency cannot work. Portions of the budget should go to training for these specialists. Acts and other programs like these must be stressed to the government so we can gain sufficient support and funding from them.

One final barrier comes simply from the fact that people are not fully aware of these programs/agencies. Since AIDS rates are only increasing, previous prevention efforts are falling short of their goals. We need to get the word out about our program. The program will be advertised in as many places as possible including bus ads, billboards, and possibly a commercial. The more people who see and hear about the program, the greater number of participants there will be.

With all of these small tactics and plans surrounding the central plan of having a program open to the public concerning AIDS prevention, we feel that noticeable results can be seen within the first few years of the start of the program. The south Bronx has proven to be an area of high AIDS rates and prevention efforts like the proposed program can help deflate those rates. With dedicated workers and a serious attitude, this program can prove to be one of the most effective for preventing the spread of AIDS.

![]()

http://www.library.fordham.edu/postcards/rosehill/greetings-bronx.jpg